The Talented Mr. Bush and a Few Good WASPs

A response to a friend: what's the difference between a guest and a prisoner?

Some years ago I met President George H. W. Bush at the scene of his birth and in my hometown.

The former president had come to visit and I, who couldn’t have been more than six years old, shook his hand. He gave me a pen and smiled. This would be the first time I would meet a president but it would not be the last.

41’s visit made the news and all the local dignitaries were there. The son of the state senator — Brian A. Joyce, who would later be indicted for corruption — was pictured in the paper. The younger Joyce was something of a rival of mine. Try as I might, and boy did I try, I could never quite best him. He was a sort of Irish son of Milton, the most Irish Catholic town outside of Ireland, and I, being neither Irish nor Catholic, had reached the limits of what was possible. Still, vestiges of the old WASP order remained and here was a living, breathing example of it.

My dad asked me how it was to meet him and I told him. “It’s not every day you get to meet a director of the CIA,” he said. I remember asking my father who or what the CIA was and in many ways I’ve been learning ever since.

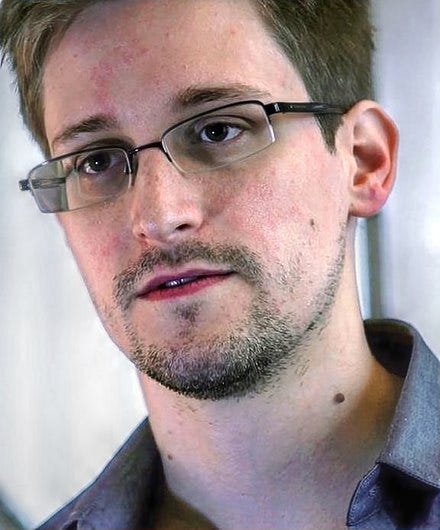

Years later my father would take this picture of me which is framed in one of my homes.

From that day forward I cheered the elder Bush. I can even do a good impression but that, well, that wouldn’t be prudent! ;-)

The younger President Bush left something to be desired — I’ve long come to the view that the closet case threw in with the neocons (or did they blackmail him? I wonder) and that was that — but the father is that sort of WASP that is both desperately needed and vanishingly in short supply.

Is his grandson the man the grandfather was? I don’t know but I’m trying to find out. I lost all respect for the incumbent when he asked me for a bribe in his office over looking the state capitol. I believe as the statesman Senator Robert Goodloe Harper did in the XYZ Affair: “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute!”

Again and again, the Bushes would pop up and usually on the side of the Anglo-American alliance. A recent book I read about the history of venture capital industry — Creative Capital: Georges Doriot and the Birth of Venture Capital — has a cameo with George H.W. Bush’s company, Zapata Off-Shore. Why, yes, the elder Bush was a startup CEO whose company innovated a mobile oil-drilling rig. Makes you think.

But to my mind the more interesting thing the Bushes did was build a proto-social network.

There’s a terrifically good exploration in the London Review of Books on all that Bush had done. The title gives it away — The Vice President’s Men by Seymour Hersh (a sort of limited hangout between the Russians and America).

When George H.W. Bush arrived in Washington as vice president in January 1981 he seemed little more than a sideshow to Ronald Reagan, the one-time leading man who had been overwhelmingly elected to the greatest stage in the world. Biography after inconclusive biography would be written about Reagan’s two terms, as their authors tried to square the many gaps in his knowledge with his seemingly acute political instincts and the ease with which he appeared to handle the presidency. Bush was invariably written off as a cautious politician who followed the lead of his glamorous boss – perhaps because he assumed that his reward would be a clear shot at the presidency in 1988. He would be the first former CIA director to make it to the top.

There was another view of Bush: the one held by the military men and civilian professionals who worked for him on national security issues. Unlike the president, he knew what was going on and how to get things done. For them, Reagan was ‘a dimwit’ who didn’t get it, or even try to get it. A former senior official of the Office of Management and Budget described the president to me as ‘lazy, just lazy’. Reagan, the official explained, insisted on being presented with a three-line summary of significant budget decisions, and the OMB concluded that the easiest way to cope was to present him with three figures – one very high, one very low and one in the middle, which Reagan invariably signed off on. I was later told that the process was known inside the White House as the ‘Goldilocks option’. He was also bored by complicated intelligence estimates. Forever courteous and gracious, he would doodle during national security briefings or simply not listen. It would have been natural to turn instead to the director of the CIA, but this was William Casey, a former businessman and Nixon aide who had been controversially appointed by Reagan as the reward for managing his 1980 election campaign. As the intelligence professionals working with the executive saw it, Casey was reckless, uninformed, and said far too much to the press.

Bush was different: he got it. At his direction, a team of military operatives was set up that bypassed the national security establishment – including the CIA – and wasn’t answerable to congressional oversight. It was led by Vice-Admiral Arthur Moreau, a brilliant navy officer who would be known to those on the inside as ‘M’. He had most recently been involved, as deputy chief of naval operations, in developing the US’s new maritime strategy, aimed at restricting Soviet freedom of movement. In May 1983 he was promoted to assistant to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General John Vessey, and over the next couple of years he oversaw a secret team – operating in part out of the office of Daniel Murphy, Bush’s chief of staff – which quietly conducted at least 35 covert operations against drug trafficking, terrorism and, most important, perceived Soviet expansionism in more than twenty countries, including Peru, Honduras, Guatemala, Brazil, Argentina, Libya, Senegal, Chad, Algeria, Tunisia, the Congo, Kenya, Egypt, Yemen, Syria, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia and Vietnam.

Bush, in other words, felt that the CIA wasn’t doing its job and so he created a new organization de novo.

The unnamed entity served the same sort of spiritual and political role as Winston Churchill’s Special Operations Executive.

Do we have the daring to do such a thing today?

Did Bush, taking over after Colby, feel he had no choice but to go around the CIA, which had fallen?

Anyway, a friend writes in and I’ve slightly edited it and added a few responses interspersed. (Note to the readers: I love getting mail.)

I met William Colby in 1994. I had been working on a documentary about Raul Wallenberg based on the newly released OSS/CIA Wallenberg file in the National Archives. I was the first journalist to see them and my Dutch TV employers wanted a story about the new documents.

The collection contained any number of documents which needed the trained eye of an experienced spook. So, I went to Richard Helms’ office and he rebuffed me. After that, I opened the phone book, found Colby’s number in Georgetown and rang him up. He turned out to be quite willing to do an on- camera interview.

Colby was affable, approachable and competent. We spent a couple of hours discussing my research.

That was the difference between Helms and Colby and why the press treated each so differently.

You speculate that Colby may have been a foreign agent because he actively participated in the Church Committee. Colby was a member of the WASP liberal establishment. I remember that period. The Viet Nam War moved the WASP establishment towards self destruction and Colby participated in that process. I don’t find much in his career which would indicate he had been recruited by the Soviets.

The same cannot be said for James Angleton. Angleton was very close to Kim Philby. The American got to know Philby during the War in London and worked closely with Philby during his Washington posting after the War. Either he knew about Philby or he was completely blind to Philby.

I suspect it was the latter. Angleton’s Anglophilia blinded him. In his “A Spy Among Friends”, Ben MacIntyre argues that Philby’s upper class connections protected him against the well grounded suspicions of British counter intelligence.

His other Oxbridge, aristocratic colleagues could not believe that Philby was an agent. He was one of them. The counter intelligence officers, on the other hand, who mistrusted Philby were red brick college, middle-class Brits. A lower class of people. What did they know?

I suppose we will get a sense in the not-so-distant future now that Ben MacIntyre’s book, A Spy Among Friends, is going to be made into a television series starring Guy Pearce and Damian Lewis.

I suspect it’s the same formulation as it has always been — the closer you are to the Crown, the closer you are to the Kremlin. This was forever thus. The wealthy Brits like those old school Russians.

These sort of close networks — MacIntrye stresses the importance of male friendship — help shape much of the world. The scholarship boys are all with us whilst the old Etonians middleman between us and the Russians and increasingly the Chinese.

There’s something quite queer about the old boys network and no, I’m not just talking about the homosexuality. It was a fashionable thing to be a Communist and good thinking people wanted to be avant-garde, elite, even. This failure of British high society to instill its toffs with a sense of duty has, I think, been one of post-War Britain’s greatest failings.

One gets a sense of this when the traitor in the film adaptation of John Le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011) tells Smiley, “It was an aesthetic choice as much as a moral one,” he says of his treachery. “The West has become so ugly.”

How you make the men who have inherited so much find beauty in their society, I don’t know.

I wonder further about these supposed defections of the British aristocracy. Might Her Majesty have kept an open channel with the Russians as she no doubt did with the Maxwells and the Epsteins of this Earth?

That much seems pretty clear when you consider that Sir Anthony Blunt was allowed to continue on in her service, notwithstanding the revelation of his treason some years later.

We aren’t allowed to think of the Monarchy having its own foreign policy so we believe the Netflix depictions of the Queen being oh so shocked to learn of Blunt’s treason. But, well, I have my doubts. I think Her Majesty wants her back channels. And why wouldn’t she? She always seems to want to know what’s going on around the world.

My friend continues:

Angleton worshipped the British aristocracy Philby could play perfectly to that and keep Angleton from ever seeing the real picture. A bit like Bill Hayden carrying on an affair with George Smiley’s wife. It kept Smiley from seeing straight, at least for a while.

I wonder what would have happened if the home-schooled, Presbyterian Allen Dulles had been posted to London instead of Angleton. I doubt Dulles would have been swept off his feet by the suave Philby.

The McIntyre book has an interesting thesis on the how Philby was recruited and how Philby met his downfall. Both involve a female Jewish Communist. McIntyre suggests that Philby was recruited by a Jewish Sparrow in Vienna in the 30’s. After a weekend of pleasure, Philby was won over. His unraveling came at the hands of Jewish heiress in London. She had made the now familiar Communist to Zionist sojourn from the 30’s to the 50’s. Reading Philby’s dispatches from Beirut, she was outraged at his anti Israel line. (After being forced to leave the Foreign Office, Philby found a job as a newspaper correspondent in Lebanon covering the Middle East) She remembered that she had met Philby in Communist groups in the late 1930’s. She took this information to counter intelligence. A former MI 5 colleague named John Elliott was dispatched to Lebanon to interrogate Philby. McIntyre thinks that Elliott’s visit was intended to warn Philby to clear out since the British establishment had no stomach for a public criminal trial. After Elliott’s visit, Philby made his escape to Moscow.

…

Interesting speculation about Colby. Not sure it works. But maybe I am just one of a bunch of journalists who liked him because he met with me.

At issue here, I think, is the question of class and its role in intelligence community.

Was scholarship boy Angleton taken in by the British aristocracy? I don’t know but I tend to doubt it. I suspect that Angleton was probably aware of Philby’s treason and that he had shared the material with Philby so that the Soviets and America could de-escalate tensions after World War II. It didn’t, alas, work, but that doesn’t mean the attempt was insincere.

Could it well have been that America didn’t take seriously HUMINT? Possibly but Angleton always did.

And how exactly did it come to pass that Philby was outed?

That, if we are to believe it, comes from Flora Solomon, a Jewish senior executive at Marks & Spencer, who, some thirty years after the event, purportedly told Victor Rothschild in 1962 that Philby was a Soviet spy.

And her reason for outing Philby as relayed in her memoirs? Apparently she objected to the anti-Israel tone of his articles from Beirut for the London Observer.

Consider me skeptical. It’s very clear that Rothschild always knew and that the Rothschilds themselves served as a go between for the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom.

Today we have so much SIGINT that you can quickly identify who belongs to what network just from their click stream or iPhone traffic.

Yes, the nerds have taken over. The old networks don't work so well as they once did. They can have their country clubs but we’ll take the country.

You have to be intelligent about intelligence.

So one wonders… was Philby a defector? Or something else?

And might there be another reason to park Philby in the Soviet Union? Could he have been spying on them and relaying it back to Britain?

One wonders if there might be other “defectors” that remain loyal to America or Britain, other “defectors” whom we are encouraged by partisans in our media to hate.

What’s the difference between a guest and a prisoner? Is it treatment? Is it profile?

In the ancient world rival regimes would take the children of nobility or even royalty into their country so as to keep their parents honest.

This finally brings me to Edward J. Snowden, who I believe to be the most famous prisoner there is.

I have always found it hard to believe that Snowden is a traitor. Mixed up? Yes. Naive? Certainly. But a traitor? No. His pedigree doesn’t suggest it.

I think he was used, his libertarianism both played and preyed upon as it so often is with us autistic nerd types.

But who could have used him? And why?

Allow me to suggest it was Glenn Greenwald, whose own history as a pornographer turned journalist raises eyebrows and hasn’t gotten the full explanation it deserves.

Brazil is a non-extradition country isn’t it?

And Greenwald’s considerable personal baggage might make us consider the degree to which he might have been subject to other motivations beyond just exposing the truth.

Why has Greenwald barely discussed Israel amidst the Snowden revelations? Curious indeed and well noted by Haaretz, the leading Israeli paper who posited several theories as to why.

Let me suggest a final theory: Greenwald is tied in with a foreign government’s intelligence. That might that explain why he was so supportive of covering the Hunter Biden laptop story, a topic I dare not tell the truth about just yet.