Impertinent Questions: How Inbred Are You? And Would You Like to Know?

Should consanguinity even be considered harmful? Genetics and the inner sorts of questions.

Dear readers: I highly recommend checking out Traitwell’s new consanguinity predictor, especially if you’ve done 23andMe or Ancestry. I am the CEO of Traitwell. Already Traitwell has published an education predictor and a covid risk predictor. We have many more in the offing. (Maybe there’s a predictor you are particularly interested in? Let me know.)

Soon we will be adding kits. If you’re worried about Ancestry.com being Chinese or 23AndMe being Russian and Chinese you need not fret. We are an American company with backing from Americans. If you’re like to learn more about Traitwell or have questions, feel free to reach out.

Check out our app here and I do hope you’ll sign up. It’s free.

My maternal grandparents’ marriage record from the state of Indiana has a curious mention of something I had never thought much about — where or not they were cousins.

Given that they were both redheads I suppose that’s a fair question. Every ginger knows the perils of walking around with another ginger in public. “Are you two related?” they ask only to be disappointed. Worse yet is when passers-by suggest I date my redheaded sister. Oh heavens.

My grandparents weren’t cousins and were married and then they proceeded to have seven children, among them my mother. All of them have red hair (though time has turned it white, as you can see.)

Like a lot of redheads I’ve gotten pressure to continue my proud people’s existence. My half-Asian daughter makes it unlikely. So too does my relationship with a half Mexican quarter Jewish quarter Italian girlfriend. It’s a little sad to think I might be the last of my redheaded line but I prefer my other traits pass on.

Red hair is a recessive trait and so if I wanted to keep it in the family I’d have to look closer to home and well, there’s something kind of fun about hybrid vigor.

Like a lot of Americans I have a visceral distaste for inbreeding. I’ve often wondered why. I don’t totally buy Steven Pinker’s view about it being hard wired into us to have an aversion. And besides, people can overcome virtually any aversion if conditions are favorable.

If it were hard wired why is incest so common in certain groups?

We have to ask ourselves rather obvious questions: Why do some of the most powerful families in the world inbreed? Is this the secret to their having amassed wealth? And if it is, when is it wise to stop inbreeding?

“You shall know the truth and it shall set you free.”

That’s what the Bible tells us but how do we even know what’s true in this era of misinformation and disinformation? Might bad information even imprison us?

Truth is linked with science. We oftentimes talk about science and what’s the best way to live — isn’t this the whole point of philosophy? — but rarely do we examine how that which we can learn from science might be readily applicable to our everyday life. Too often those insights are published and quickly forgotten, left to sit in some dusty library. The saddest fate of all is how many great ideas or products have been lost.

Now I’m been enamored of using science to make better decisions. The Russian-linked cult of “Less Wrong” gets it half right but we don’t want to be merely less wrong. We want to live well. To thrive, even.

Decisions come from better information and information, as Claude Shannon teaches us, is simply a question of 0s and 1s. Even the most complicated things in the world — DNA — can be turned into data.

Data is how you can live well. I’m particularly enamored of the DuPont family, who seems to have taken noblesse oblige seriously. My father went to Kent with one of them. Of the super rich kids, “he was pretty nice,” reports my father.

Their slogan was "Better Things for Better Living...Through Chemistry." (Now it’s the somewhat lackluster — "miracles of science.”)

I’d amend that only slightly — “Better things for better living…through data.” One of the tragedies of the modern world is how so many of the data companies are exploitative but the DuPonts were anything but. You can see vestiges of their generosity throughout the United States and up to the present day. Indeed we may owe the presidency of Joe Biden to the DuPoint family. (Biden’s love of the DuPont family and the vicissitudes of their family fortune and its attendant affects on Delaware have left quite an impression on our 46th president, if the Wall Street Journal is to be believed.)

Were I to be cheeky I might even say “better living through cousin marriage.”

After all, the DuPont family, which is itself quite inbred, is one of America’s longest serving dynasties. And deliberately so. The first Pierre Samuel du Pont favored cousin marriage to preserve the “honesty of soul and purity of blood.” In recent years some of the DuPonts may have gone a tad mad though from inbreeding or some other reason it’s hard to say without a peek at the old genome.

By their fruits ye shall know them and the DuPonts have been particularly productive. They’ve answered our nation’s call often and through their friendship with President Thomas Jefferson was essential to its continued expansion. Later they charge only a dollar above costs for helping the United States build the atom bomb.

For those suitably interested I highly recommend the documentary on the Du Pont family.

Should you do as the DuPonts do if you want to build dynastic wealth?

My colleague Gavan Tredoux, when I don’t have the whip cracking on him, is something of an amateur historian into the history of science and genetics. He delights in spending his vacation time in the archives of some hitherto unexplored library and the insights he gleams from them upend our understandings.

If you are an amateur archivist do please reach out. We have a lot to discuss. Eventually I’d like to build a real community of archivists. Think of it as a kind of Task Rabbit for archival material.

One of his books, Comrade Haldane Is Too Busy to Go on Holiday: The Genius Who Spied for Stalin, is very good though I think Haldane was more of a limited hangout betwixt the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union. In any event I value his contributions at Traitwell.

Here’s what he’s written for our Traitwell Substack. I commend it to your attention. I continue it below, with slight edits.

It is commonly believed that inbreeding is harmful. Marriage between close relatives is forbidden by most legal codes. This covers brother-sister and parent-child incestuous unions, which are almost always strictly prohibited, but it often extends to forbidding first-cousin marriages too. In the United States, first-cousin marriage is a criminal offense in nine states and subject to civil sanctions in a further 22 states. There are clear reasons for the prohibition.

Weighing the Genetic Risks

Humans reproduce sexually and are "diploid," carrying two copies of (almost) every gene, one from each parent. A mutation in one of these copies can occur without necessarily showing ill effects, in which case it is silently passed down from the carrier to about half the offspring on average. However getting two copies, one from each side of the family, can be harmful. Marrying a relative increases your chances of getting two copies of a mutant gene. For first cousins, the risk of developing a disorder is multiplied, but this depends on how common the mutant gene is in the breeding population that one is drawn from.

If a recessive gene is found in 10% of people, and your parents are unrelated, then the chance of getting the disorder is only 1%. However if your parents are first cousins, then the chance is higher, at 1.56%. Your risk is multiplied by 1.6. Counter-intuitively, the more rare the gene is in your gene pool, the larger that multiplier becomes. If the frequency is 5%, then offspring of first-cousins increase their risk from 0.25% to a 0.547% chance. That is 2.2 times the risk. If the recessive gene is ultra-rare, occurring in say 0.5% of the population, first cousin marriage increases the risk from 0.0025% to 0.00336%, which is 13.4 times the risk.

Notice though that these are pretty small numbers anyway. From the point of view of an individual, a risk of 0.00336% may seem to be practically zero. A moderately large number multiplied by an extremely very small number is still a very small number. But then one must weigh up the consequences of actually getting a disorder. If it is painful and leads to a very early death, even a small chance of getting it may be unacceptable, and one may choose to do everything possible to decrease the risk. Still, life is full of risks. Driving to the beach to buy an ice-cream and soak up some sun carries a non-negligible risk of a car accident or other misfortunes, yet many choose to take that risk as the price of living. Your cousin may be related to you, but perhaps she is also very pretty (a proxy for good health), exceptionally smart (you hope your children will be too) and wealthy (money is always welcome). Perhaps, too, if either party is unhappy they can get redress from relatives, who are not strangers. Plainly a large element of personal preference exists in the process of trading off risks.

This calculation is rather different at a societal level. Repeated inbreeding builds up consequences over time, becoming a burden. Indeed almost all sexually reproducing animals avoid close incest purely by instinct. The aversion that humans feel to incest is certainly instinctual. It could not have evolved otherwise, since each individual does not have enough time or experience to work out the long-term consequences of close inbreeding.

Historical Examples of Inbreeding

Given that this is so, it may be surprising to learn that some degree of inbreeding has been widely practiced in human history, and is still practiced today. Influential dynasties have tended to inbreed to a certain extent over prolonged periods. A famous case is the Rothschild family of banking magnates. Over two centuries, the 18th and 19th, about a third of all marriages involving that family were between first cousins. As their progeny have shown, there do not seem to have been marked ill effects. Or, if there were, they were compensated for by other virtues, such as keeping wealth intact, leveraging trust, and acquiring many other favorable genes. Similarly the hereditary “rebbes” of the Lubavicher Hasidim, a sect of Orthodox Jews from Belarus, married mostly cousins since the 18th century and prospered up until the present day.

Many other examples could be given, not the least of which is the Darwin family. Charles Darwin married his first cousin Emma Wedgwood and produced very distinguished children, the males of which became first-rate scientists in their own right. Their relatives the Galtons were from Quaker stock, a nonconforming sect that became isolated within English society for centuries and became markedly inbred. Their most famous product, the scientist Sir Francis Galton, has a family tree that resembles a fishing net in places, as multiple lines cross over. Yet the family prospered in gun manufacturing and banking, a more traditional Quaker occupation (Barclays and Lloyds will be familiar names to many), and Francis is recognized as a genius. Grieg and Rachmaninov both married first cousins, as did Albert Einstein, Edgar Alan Poe, H. G. Wells, Mario Vargas Llosa and Friedrich Hayek. Thackeray, John Ruskin, and Lewis Carroll were products of cousin marriages and many popular Victorian novelists like Dickens and Trollope made it a theme of their fiction.

On the other hand, many other examples can be given where inbreeding has had harmful effects, in the sense of heightened rates of genetic disease and peculiar disorders. Ashkenazi Jews are relatively inbred and have much higher rates of Tay Sachs disease and certain other genetic disorders than other populations do. The Amish, Hutterites and Mennonites in America are also relatively inbred, and have elevated rates of certain genetic conditions. A lot depends here on how long a group has been practicing inbreeding and other variables. Often the presence of a founder or set of founders who carry particular diseases will be influential. Thus Afrikaners in South Africa have elevated risk of heart disease because of influential founders who brought a genetic condition to the country in the 18th century. The relatively small breeding population led to its rapid propagation.

An important influence on inbreeding is the broader mating system. If there is extensive clan structure then multiple lines of relations start forming and reinforcing. A first cousin may be much more than just a first cousin in such a scenario, because more distant lines of relationship accumulate. Anyone who reads a textbook on population genetics will be struck by the very first assumption made, which is that the population in question mates randomly. But real human populations do not do this. It is a simplifying assumption to make the problem tractable, as all models must do. Physicists assume billiard balls are perfectly elastic. But billiard balls really are approximately inelastic, whereas in highly structured populations, with clans marrying within clans, or within castes, the simplifying assumption of random mating may be violated to a very substantial degree.

Outbreeding Considerations

Does it pay genetically to deliberately outbreed, even to the extent of seeking out cross-racial mating? There is some evidence that all things being equal otherwise, there is some benefit to being deliberately outbred. This is often referred to a hybrid vigor, or heterosis. A famous study conducted in Hawaii by Nagoshi and Johnson (1986) found some support for a 4 point average IQ gain among the offspring of European-Japanese offspring. However in a large breeding population, recessive genes with clearly bad effect are pretty rare, so that far more is to be gained from avoiding close inbreeding, all else being equal, than there is from deliberate outbreeding. Which is to say, you don't have to go all that far afield.

The key qualifier is "all other things being equal." As stated above there may be tradeoffs to consider. Especially if you are a Rothschild. Or a Darwin.

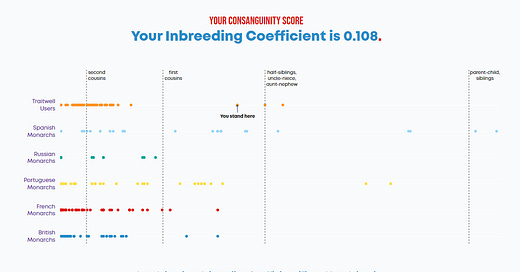

Find Out How Inbred You Are

To find out how inbred you are, click on over to traitwell.com/consanguinity and upload your DNA. It is free and informative. We can directly estimate from internal examination of your DNA approximately how inbred you are. We also show you where you stand with respect to other individuals and historical examples. We don’t even need to know your family tree. It's all right there in your genes. This is actually the most accurate method for estimating inbreeding, since pedigrees usually contain errors.